This, the latest post on the Toxic Plants blog, can be found on the blog’s new home at toxicplantsblog.blogspot.com. Please feel free to visit. There will be no more posts on this, the old blog. Have a great day.

Allotment reloaded – Revenge of the Frankencarrots

I just wanted to let subscribers to my old blog know that I have posted my first new post on the new blog, “Revenge of the Frankencarrots”. You can find this at https://toxicplantscouk.blogspot.com

The new blog has more of a focus on growing edible, medicinal and toxic plants and less of a focus on peak oil and societal collapse – hence the change of name. Peak oil and societal collapse are still coming to a civilization near you, of course, but not just yet, and I’m hoping that my fruit trees will have chance to mature before they arrive. You can now subscribe to the new blog (if you want) in the same way that you could subscribe to the old one, and be notified when there is a new post, which will be once every three months as before.

The reason for the rather clunky name of the blog is because my preferred URL, toxicplants.blogspot.com, is not currently available. Until very recently it was occupied by spammers who were peddling, shall we say, unusual videos. Now that the spammers and their dubious wares have been thrown off the site, there is a 90 day grace period after which I am hoping to take over the name.

Have a great Christmas and New Year.

The end of an era

With the Winter Solstice approaching, it’s that time of year when we look to the past and the future, review our successes and failures during the old year and try to predict what the New Year might bring.

I’d like to start off with an announcement: this will be my last post on this blog as I am planning to shut down this blog and the accompanying Post Peak Medicine website early in the New Year. To explain why I am doing this and to put it into context, I would like to take you on a super-fast tour through the 300,000 year history of our species, compressed into about 10 minutes.

Our species – Homo sapiens – evolved about 300,000 years ago, and until about 10,000 years ago we lived a roaming, hunter-gatherer life. We occupied a place at or near the top of the food chain and coexisted with a great many other species without threatening their existence or the integrity of our shared habitat.

About 10,000 years ago the first human civilisations emerged, based on sedentary agriculture and the domestication of plants and animals, initially in the Middle East between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in an area which corresponds to parts of modern day Iraq, Kuwait, Syria and Turkey. The first settlements were founded on the fertile lands bordering the rivers and were sustainable, but as the population grew and the area of cultivated land increased, it became necessary to develop irrigation channels to bring water to the drier land further away from the rivers. This proved to be unsustainable as the soil became increasingly saline and the settlements in those areas declined – probably the earliest example of the diminishing returns of technology.

Over the next 10,000 years, as numerous civilisations and empires rose and fell, the human population of the planet gradually increased and our effect on local ecosystems became increasingly noticeable. For example, large areas and sometimes whole countries were deforested in order to create more arable and grazing land to feed the growing human population – the United Kingdom being a case in point. Some civilisations collapsed through over-population and severe environmental degradation, for example, those of the Mayans and Easter Islanders. Nevertheless, these failures were the exception rather than the rule. Most human civilizations continued to exist sustainably, to coexist with other species and not permanently damage the carrying capacity of the environment.

The next major turning point for human civilisation came in the mid-18th century with the exploitation of fossil fuels, starting with coal in Britain, to power new inventions such as the steam engine, spinning and weaving machinery and new iron and steel manufacturing processes. The Industrial Revolution improved the quality of life for most people who participated in it, and made a few industrialists fabulously wealthy, but it was unsustainable from the start. The earth only has a finite amount of fossil fuel, and once it has been burnt and released its energy, it can never be re-burnt.

The world’s human population at the start of the Industrial Revolution was about 1 billion. With increasing quality of life, better sanitation and more efficient food production, the population increased to around 2 billion in 1930, 4 billion in 1974, 6 billion in 1999 and 7.8 billion today. It has more than doubled during my lifetime. Not only is this rate of increase unsustainable, but it is unsustainable for the numbers to continue at the current level even without any further increase. Most of today’s population is fed by the burning of fossil fuels and depletion of topsoil, minerals, fresh water and fish in the ocean, all of which are non-replaceable within any realistic timeframe. When these finally go away we will find out what the carrying capacity of the planet really is, and my guess is that it’s probably less than the one billion people who lived at the start of the Industrial Revolution when fossil fuels, topsoil, fresh water and fish were abundant.

The people who were around at the start of the Industrial Revolution couldn’t possibly have known that they were setting human civilisation on an unsustainable course. They had no way of knowing that burning coal in Britain would eventually lead to global warming, the melting of the polar ice caps, sea level rise, 10,000 mile long fossil fuel powered food supply chains and the death of the Great Barrier Reef – how could they? However, increasing numbers of warning lights have been flickering on our civilisation’s dashboard since the 1950s. These include M King Hubbert’s warning about peak oil (1956), Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), the Limits to Growth report (1972), the 1970s oil crises (1973 and 1979), the beginning of the bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef (1980), the collapse of the Newfoundland cod fishery due to over-fishing (1992), the Great Financial Crisis (2008) and increasingly strident warnings about climate change and species extinction – including possibly our own. Most of these warnings have been ignored, or at least, not acted upon effectively.

I came onto this scene rather late. Born in 1959, I didn’t take much notice of most of the above, assuming, as most people did, that governments had it all in hand and knew what they were doing. In 2008 I became aware of the existence of peak oil and the impossibility of perpetual growth on a finite planet, and I decided to try to do something about it. I thought that perhaps if I wrote a book about how one might create a workable healthcare system in a post peak oil society, it might wake up and persuade some people. Hence, “Post Peak Medicine” (the book and website) were born in 2010 and have been online ever since. In the last ten years, to the best of my knowledge, they have woken up and persuaded precisely nobody, although a lot of people have read them who were probably thinking along those lines already.

Food, fresh water, energy, minerals, manufactured goods and humans are all going to decrease in quantity from now on until they reach a new equilibrium at a fraction of their current levels, which will probably be a few hundred years in the future. This is going to happen whether we like it or not, and whether we plan for it or not. Reality requires it, and is going to do it for us if we don’t do it for ourselves. Despite this, governments, economists, the mainstream media and the general public are still calling for more material, economic, energy and population growth, although there has been a shift towards the rhetoric of “green energy”, “green growth” and “sustainable growth” and much talk (although considerably less action) about the need to limit climate change.

Ten years is enough. If the world has ignored 60 years of warnings including 10 years from me, it is unlikely to start listening any time soon, I’m not planning to spend any more time or energy trying to persuade it, and I’m closing down the Post Peak Medicine book, website and blog. Instead, I’m directing my energy into learning how to grow food for myself and my family and developing my knowledge about toxic plants (see my previous post) in the hope of developing safe and effective plant-based anaesthetics which may be of some practical use to people in the future. I’ve set up a new website and blog at toxicplants.co.uk and toxicplantscouk.blogspot.com respectively, and I’ll continue to publish a blog quarterly, with the emphasis (as the name suggests) on toxic plants, and maybe a few edible plants as well. Please feel free to visit and comment!

Have a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Or a good Winter Solstice if that’s your preference.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

The care and use of toxic plants

First an important announcement:

DO NOT TRY ANY OF THESE TECHNIQUES AT HOME, OR ANYWHERE ELSE. YOU WILL PROBABLY END UP DEAD. IN FACT, TO BE ABSOLUTELY SAFE, DON’T READ ANY FURTHER.

That’s the legal stuff taken care of, so now I’d like to explain what this post is about and why I’m writing it. It’s not about herbal medicine in the conventional sense. Most reputable herbalists wouldn’t touch most of these plants with a proverbial barge pole because they’re too toxic and/or illegal. I suspect that a lot of mainstream herbal medicine works by a combination of counselling and aromatherapy, and before I get a lot of angry emails from herbalists, I want to make it clear that I’m not being disparaging. Many of my patients in my family medical practice come to me because they are stressed, anxious or depressed. The best thing for them would probably be a sympathetic ear and a harmless but nice smelling herbal concoction. However, I am afraid I am terribly bad at this sort of thing. (“Wife left you, you got fired from your job and you’re having a midlife crisis? Pull yourself together, man. Have some antidepressants.”).

But in a societal collapse scenario, what if you need a gangrenous leg or appendix removed, and something powerful to knock you out for the surgery? During the Napoleonic Wars, most unpleasant operations such as amputations were performed without any anaesthetic or pain relief, other than a swig of brandy if you were lucky. The use of morphine, ether and chloroform for anaesthesia and pain relief only became widespread during and after the American Civil War. The ability to provide pain relief for surgery is one of the hallmarks of a civilised society. Toxic plants may not be as good as modern anaesthetics, but they are better than nothing, and certainly better than jasmine or lavender. The toxins are probably a defence mechanism, evolved to discourage animals from eating them, but if they are used in carefully controlled conditions they can be beneficial. I’ve been prescribing toxic chemicals for people all my working life (for example, twenty Paracetamol / Acetaminophen can be a fatal dose) so I feel quite at home working with toxic plants.

A particular problem with toxic plants is the narrow “therapeutic ratio”; that is, the difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic or fatal dose. Calculating the correct dose is made all the more difficult by the fact that the same amount of herbal material may contain different amounts of active ingredient depending on the strain of plant, the climatic conditions, the time of harvest and the method of preparation. These plants should only be used medicinally by experienced people, only a small dose given at a time, the patient should be closely monitored, and resuscitation equipment should be available including cardiac and respiratory support.

All the plants you see here were photographed by me in the Isle of Man, in my garden, allotment or in public places.

Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger)

Grows very easily from seed. Key component of “witches flying ointment” as used by European witches from the 1400s onwards. Other common ingredients of the ointment included jimsonweed (see below), wolfbane, mandrake and opium poppy. Some of these ingredients may act in a synergistic way, but the exact recipe and the proportions of the ingredients were probably handed down by word of mouth and have been lost. As this is a family blog and I don’t want to scare the children, I’m not going to go into details of how the witches used their flying ointment. You can look it up on Wikipedia if you want. It sounds like those old witches knew how to have fun. Anyway, I digress. The point is that it put them into a trance-like state; an effect which could possibly be modified for use as a general anaesthetic.

Its toxicity is due to a mixture of toxic alkaloids including hyoscyamine, atropine, tropane and scopolamine. Anecdotally, ingestion of henbane is said to have caused some fatalities but I was unable to find any definite documented case where this has occurred. The lethal dose is not known.

Jimsonweed / Thornapple (Datura stramonium)

A key ingredient of “witches flying ointment”, see above. Jimsonweed is not native to the United Kingdom, although specimens appear here sporadically, probably due to imported birdseed. That is probably why I found one such specimen (photographed above) growing wild on my allotment. It is native to Central and North America, and its common name “jimsonweed” is an abbreviation of “Jamestown Weed”. Apparently some English soldiers consumed it while suppressing a rebellion in Jamestown, Virginia in 1676 and spent several days in a trance, remembering nothing when they awoke.

I saved its seed and tried to cultivate it the following year, but this proved surprisingly difficult. I planted at least 100 seeds, but only six of them germinated, and the seedlings were sickly and never reached maturity. This may be because in the wild, the seed is spread by birds and carried in their droppings, and the acids and enzymes in the birds’ digestive tracts probably help to activate the seed and promote germination. Next year I will try some pre-treatment of the seed before planting, for example soaking in lemon juice, or scarification (scraping away some of the outer coating of the seed). I’ll let you know what happens.

Its toxicity is due to a similar combination of alkaloids found in henbane (above). Numerous non-fatal poisonings and at least two fatalities have been documented. The two fatalities were in adolescents age 16 and 17 who drank jimsonweed tea and alcohol in the Texas desert in 1994 and were found dead the next day. It is unclear whether the deaths were due primarily to the jimsonweed, alcohol, exposure or a combination of all three.

American mandrake / Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

I already mentioned this in my last post, so I’m only going to mention this briefly here. It is not a true mandrake (Mandragora officinarum) which is a plant native to the Mediterranean region and to which it bears a superficial resemblance. The American mandrake contains podophyllotoxin, an effective treatment for warts and verrucae, which is used today in commercial preparations.

I grow most of my toxic and medicinal plants on my allotment, but this specimen is shown growing by my garden wall. This is because, in October 2018, I sent off for some mandrake root from a specialist nursery. When it arrived, I hadn’t yet prepared a permanent planting site for it, so I dug it in beside my garden wall for safekeeping, intending to transplant it the next spring.

When spring 2019 arrived, I spent twenty minutes grovelling around elbow deep in dirt, but I could not find that damned piece of mandrake root. Eventually I gave it up for lost, assuming that it had rotted away over the winter. However, when spring 2020 rolled around, I found growing beside my garden wall…an American mandrake, in the exact same spot where I had lost my piece of mandrake root 18 months previously. So now I have carefully marked the spot and I will transplant it into the mandrake bed in spring 2021. Moral: gardeners need a lot of patience.

White bryony / English mandrake (Bryonia alba)

This is another “mandrake” which is not really a mandrake. Unlike the Mediterranean mandrake ( Mandragora officinarum) it is native to the British Isles. Its turnip-like roots contain a similar cocktail of toxic chemicals to the Mediterranean mandrake but it is much cheaper and easier to obtain in Britain, and in medieval times the roots of white bryony were often passed off as Mediterranean mandrake by fairground charlatans. All parts of the plant contain the tropane alkaloids atropine, scopolamine, hyoscyamine and bryonin, similar to jimsonweed and henbane. Forty berries is said to be a fatal dose in humans. It used to be a key ingredient of “witches flying ointment”, and potentially could be used as a component of an anaesthetic.

White bryony, like asparagus, grows as separate male and female plants. The herbally knowledgeable among you will see immediately that the plant pictured above is a female plant because it is forming berries under the flowers (the male plant would produce flowers and pollen but no berries). I will try to get a male plant to keep it company.

Woody nightshade (Solanum dulcamara)

A perennial woody vine which grows in woodland margins. The juice of the berries was rubbed on warts, to cure them. Whether this treatment is effective is hard to say. The berries are moderately toxic: the active principle is solanine which can cause convulsions and death if taken in large doses. Anecdotally it is said to have caused a number of fatalities in children from eating the berries, but I have been unable to find a confirmed report of a child who died in this way, or how many berries are a fatal dose. It is distantly related to the potato, which is why you should never eat green potatoes: they form solanine in their skins.

I collected some berries from a wild specimen growing on the island but I was unable to germinate any of the seeds from the berries, probably due to the same difficulty I had with jimsonweed (above). However, cuttings taken from the plant rooted well and grew vigorously.

Opium poppy (Papaver somniferum)

This is the last of the “witches flying ointment” ingredients which I am going to discuss today, and the most illegal. The addictive and overdose potential of opioids is well known, particularly in the light of the opioid crisis in North America; however, most of these adverse effects result from the use of concentrated and/or synthetic opioids such as oxycodone, heroin and fentanyl, rather than raw opium. In some countries (such as the UK) it is legal to grow opium poppies but illegal to extract opium from them. In others (such as Canada) it is illegal even to grow the poppies. Make sure you know what the law is in your area. I would like to leave you with this photograph of opium poppies planted by Douglas Borough Council in the Marine Gardens on Douglas Promenade. They have grown opium poppies there every year since I came to the island. Is there something the Council is not telling us?

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

Internet addiction

You may have noticed that my posts here have been a bit light recently – only four in the last 12 months – and to explain why, I would like to tell you about a surreal online experience I had about a year ago.

I was on a mainstream news website when a moderately interesting article caught my eye and I posted a brief comment about it. I can’t remember what either the article or my comment were about, except that neither of them were particularly important. The point is, it drew a swift and angry response from another poster who I will call Angry Woman.

I was puzzled by this because I thought my post was quite innocuous, so out of interest I looked up Angry Woman’s profile to see what I had done to annoy her. Her profile indicated that she had posted 37,000 comments on that website alone (by comparison, I had posted about eight). My jaw literally dropped. 37,000? Really? How does she find the time? Does she not have a daytime job to go to, a family to look after, a garden to tend? And what purpose does she think her posts will serve? Does she think she will change the world? Has she ever changed her own mind? And that is probably just the tip of the iceberg: she quite likely also vents her spleen on other news websites, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp and so on. She is almost certainly an internet addict, like the people who walk round with their faces in their smartphones, oblivious to the real world.

Needless to say, I didn’t try to engage Angry Woman in any further online dialogue, which would have been pointless. Instead, I took a critical look at my own online activity. I have a daytime job, a family and a vegetable garden, all of which take a lot of looking after, and I periodically write this blog. I only have 24 hours in my day: how much time can I justify spending on online activity? There is no right or wrong answer to this as everyone’s circumstances are different, but after giving it some thought I came up with these rules of thumb for myself:

Time spent reading, watching or listening to mainstream media on or off line: 5 minutes daily. That’s just enough time to scan the headlines. It’s useful to know what the mainstream media thinks are the important issues of the day (which are not necessarily the actual important issues of the day) but most of what follows the headlines is nonsense and not worth spending any more time on. Mainstream journalists rarely seem to ask obvious questions or follow up obvious inconsistencies, and for good reason: they would probably be fired for rubbing up the wrong people the wrong way.

Time spent commenting on websites: nil. I am giving that up altogether. It seems that mainstream media websites, and environmental websites like Resilience.org and Deep Adaptation, are increasingly populated by Angry Woman clones who are prolific posters and seem to enjoy picking arguments and trading insults. I have better things to do with my time, and it is particularly disappointing when it happens on environmental websites where we are all supposedly on the same side. Environmental debates, like political debates, seem to be increasingly polarised. Maybe this is what happens when a society begins to decline. However. the standard of discussion on personal blog sites run by the owners (like this one) seems to be higher, so I may continue posting very occasional comments on those.

Time spent on social media: 10 minutes daily. I have a Facebook account with the privacy and security settings cranked up to maximum, so that it is invisible to search engines and can’t receive “friend” requests. I only use it for looking at specialist discussion groups and commercial suppliers, mostly related to vegetable gardening. I have never had a Twitter or Instagram account and I don’t intend to start now. I was talked into installing WhatsApp by a co-worker, but had to uninstall it almost immediately as people started sending me messages which I never got around to reading. The only social media site I use regularly is Manx Forums which is an online discussion site for residents of the tiny Isle of Man, where I live.

Time spent posting photos of cute babies, children, holidays, animals or selfies: nil. I had a bad experience with an online photo of myself a couple of years ago and wrote about it here. Since then, I have ensured that (to the best of my knowledge) there are no photos of me anywhere on the internet.

Time spent writing this blog: one post every three months. Hence the rather light posting you may have noticed recently. So much of my time is spent on work, family and tending my allotment that one post every three months is the most time I can justify spending on it. I don’t earn any money from it: I just do it in the hope that a few people might find it entertaining, and an even smaller number might find it useful.

Time spent writing books: varies depending on the season. I would like to leave a useful legacy when I depart this planet (not on Elon Musk’s space rocket to Mars; I am talking about the other thing) and I am currently working on “Medicinal Plants of the Isle of Man” illustrated by plants growing in my own garden and allotment. I am photographing the plants myself partly for copyright reasons, and partly because if it can’t be found or grown on the Isle of Man then it probably shouldn’t be included in the book. I hope future healthcare providers may find it useful. All books and other materials I have created are available for free here.

Continuing in that vein, my next post (in three months) will be about “Care and Use of Toxic Plants” and here is a photo of an American Mandrake (Mayapple; Podophyllum peltatum) taken in my garden this spring. American Mandrakes are rather drab, inconspicuous plants which most years put out just one leaf. However, occasionally if the plant is feeling unusually energetic, it puts forth two leaves followed by a tiny flower. You can see the flower bud in this photo, forming in the junction between the two leaves:

and the flower in this one:

The roots contain Podophyllotoxin, which is a highly toxic chemical used for treating warts and verrucae. Applied externally, it makes them shrivel up; taken internally, it would probably do the same things for your internal organs and is not recommended. More about this and other toxic plants in September.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

Allotment Reloaded – The Mistakes Edition

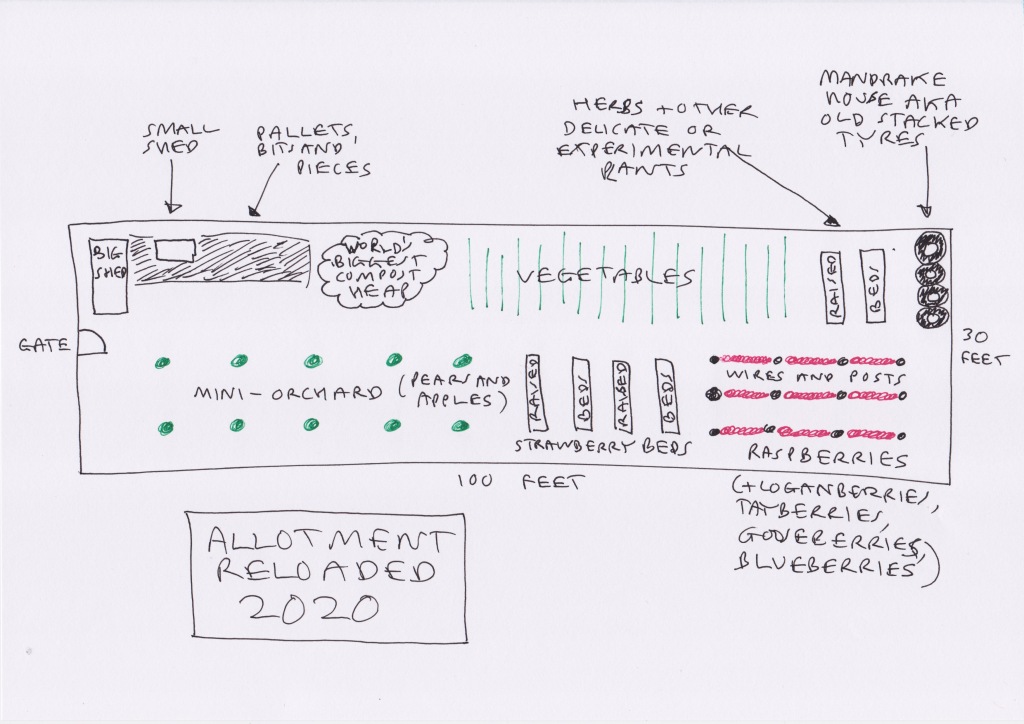

Those of you who have been following this blog will know that I acquired an allotment this time last year – a 30×100 foot plot of land rented from a local farmer for the purpose of growing fruit, vegetables and flowers. You will also know that one reason I decided to do this – apart from the fact that it’s enjoyable for its own sake – is because I can foresee food shortages in the years ahead, so learning how to grow your own food is a sort of insurance policy. So I’m trying to prove to myself and my family that it is possible to grow a significant proportion of your own food yourself. Or maybe I’ll prove that it’s not possible, depending on how things work out.

If you are going to try growing food, now is the time to start, because you are going to make lots of mistakes to begin with, and it’s better to get your mistakes out of the way while they don’t matter than to depend on a food crop for survival and then have it fail because of something simple you did wrong. I made a ton of mistakes in my first year, and I’m going to list some of them here, but rest assured, you will make lots of completely new mistakes of your own which I haven’t even thought of. It’s a good idea, at the end of each season, to make a note of what grew well, what grew poorly, what mistakes you made and what you could have done differently. Fortunately Mother Nature is forgiving (up to a point, provided you don’t take her too much for granted) and every Spring you get the chance to start afresh and do better this year.

My biggest mistake last year was failing to get the balance right between planting and aftercare (mainly watering and weeding) with the result that at least 50% of my effort was wasted. 30×100 feet is a large plot to cultivate if you’re not used to it and I was rather over-ambitious, using a mechanical rotovator to prepare the ground over the entire plot and then planting row after row of vegetables. However, while I was planting halfway along the plot, the weeds were already smothering the crops I had planted at the top end, and by the time I finished planting at the bottom end, some of the crops I had planted half way along had died from dehydration because I was too busy planting new crops to water them.

So you have to tailor your activities to the size of the plot and how much time, realistically, you are able to spend on it. In my case, the demands of work and family mean that I can spend at most half a day a week tending it. So this year I’ve planted half the plot with low-maintenance permanent plants – fruit trees, strawberries, raspberries and other soft fruits – and I’ve left room between them to get an electric lawnmower in to deal with the weeds. One quarter of the plot is used for storage – large shed for garden tools, small shed for the lawnmower, hard area for hosepipes, watering cans, large pieces of wood and glass and other bulky things which can be kept in the open, and the all important compost heap – so I’m only doing intensive vegetable cultivation on the remaining quarter of the plot.

Here is a plan of my allotment at the start of this season:

And here is a photo of the soft fruit area:

I have reserved a small area for “herbs and other delicate or experimental plants”. I’m not going to say too much about this now, because it’s probably going to form the subject of a future blog post or even a book, but I’m interested in herbal medicine and I’m planning to grow a number of unusual, not to mention toxic, medicinal plants. I’ve positioned this area at the far end of the allotment, furthest away from the gate and curious eyes and hands. Mandrakes, for example, have long tap roots and don’t like being too cold or wet, so I’ve set up some stacks of old tyres to grow them in, which will give them fairly warm dry soil and plenty of space below ground:

A friend delivered a big pile of farmyard manure for me which I’m gradually working into the plot:

Our resident tame robin, which shows up as soon as I start digging in order to look for worms, and which has absolutely no fear of people:

Next up: don’t believe the instructions on seed packets. They are a rough guide only: you have to pay attention to your own soil and climate conditions, do some trial and error and experience a few failures. Case in point: peas. Peas are tricky b******s, although you wouldn’t think it to look at them. “Plant outdoors from January onwards”, it says on the packet, making it sound so easy. Yeah, right. I tried that and most of the seeds rotted – I got about a 5% germination rate. I tried again in seed trays – same thing. So then, after doing some research on the internet, I germinated the peas in a plastic bag in the garage, then planted them in seed trays after they had sprouted. Result: I still only got about a 25% germination rate, but at least I knew which ones had germinated and I was able to plant those.

The basic problem is that I live on the Isle of Man which is on the same latitude as Labrador in northern Canada. It’s considerably warmer than Labrador thanks to the Gulf Stream, but we still only get a short and fairly cool growing season. So although planting seeds outdoors in the middle of winter may be fine in Southern England, it just doesn’t work here, and to maximise the chances of success most seeds needs to be started off indoors, then grown on under glass, and early enough in the growing season so that the plants have time to mature. It also gives them a head start on the weeds and pests.

Some plants I tried to grow last year were a complete bust, producing no ripe fruit at all, particularly tomatoes and peppers, which are basically plants of hot climates. I’m not going to try to grow peppers again, but I have found a variety of cherry tomato which seems to do reasonably well in our climate, so I’m going to try to grow those again and this time protect them with some old panes of glass (which you can see in the herb garden picture) until the weather warms up.

Pest control is something I’m going to pay far more attention to this year. Last year, of the 50% of my crops which survived the drought, weeds and my general inattention, at least half was eaten by pigeons, mice, birds, slugs and snails, and my crop of Brussels sprouts failed completely when it was chewed off at the roots by cabbage root fly. I’m trying to avoid using chemicals on my plot, partly because it’s bad for the environment and partly because I’m trying to simulate growing food in a post-industrial, post-chemical environment. But that does mean that I’m going to have to use lots of mechanical barriers like polytunnels, bird nets, rabbit fencing, mousetraps and slug tape.

Incidentally, the Brussels sprout failure is a reminder to have a mixture of plants, not a monocrop, so that if one plant fails due to adverse pest or climate conditions, hopefully most of the others will thrive. For an example of what not to do, think “Irish potato famine”.

One mistake I nearly made, but caught it just in time, was planting two identical pear trees. Having ordered and planted them, I was reading a gardening book when I found, buried in the small print, advice to plant different varieties of pear tree so they can cross-pollinate each other. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, shocking though this may sound, pear trees have sex with each other when we aren’t looking, but only with a different pear tree, not one of the same kind. If they don’t have sex they don’t produce fruit. So I quickly ordered and planted another two pear trees of different varieties, and now all is well, but that was a near miss. I could have ended up ten years down the line with two mature pear trees producing flowers but no fruit.

And finally, think about where things are best situated so you don’t have to move them around later. To some extent this is inevitable as a garden is always a work in progress, but in the last four months I’ve moved fruit bushes, compost heaps and strawberry beds from where they shouldn’t have been to where they need to be, and I could have saved myself a lot of work. However, I think I’ve got the spacing of the new fruit trees about right.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

Predictions for 2020 (and beyond)

As the winter solstice and the season of Yule approach, bloggers like me start to peer into the murky waters of the future and try to make predictions for the year ahead, so here are mine for 2020 (and beyond).

To start with, as per my predictions this time last year, we live in an unstable world at which anything could happen at any time to upset the status quo. It would only take one mentally unstable head of state to start lobbing missiles at another, and to be honest, I don’t have any particular head of state in mind because there are too many potential candidates in the field. Just choose your least favourite deranged head of state and let your imagination do the rest.

But assuming that doesn’t happen in the next 12 months, we can get some insight into the way things are going by looking at the outcome of the British general election which took place on 12 November this year. As you may know, the result was a landslide victory for the Conservative Party, a crushing defeat for the Labour Party, and significant gains for the Scottish National Party. For overseas readers, the Conservative and Labour parties are somewhat similar to the Republican and Democratic parties in the USA, respectively.

The election was overshadowed by the Brexit debate (Britain’s exit from the EU) which has been rumbling on for over three years and resulted in political gridlock. The Conservatives promised to “get Brexit done”, the Scottish Nationalists were opposed to it, and Labour sat on the fence and said they would hold another referendum. However, there were other issues exercising the minds of the voters apart from Brexit, which I will discuss below.

If you live in the United States, or Canada, or Australia, you may be thinking “what relevance is the British general election to me?” but you will probably find, when your election time comes around, that your politicians are grappling with, or attempting to evade, the same issues. I’m going to categorise those issues in terms of the three E’s: Energy, Economy and the Environment.

Energy

I’m going to lay out the election manifestos of the three parties I’ve just mentioned on the table like a pack of Tarot cards and see what we can divine about what the voters liked or didn’t like about them. There is surprisingly little difference between the parties’ energy policies. All three parties promised to improve the energy efficiency of homes and transition away from fossil fuel energy and towards “clean” or renewable energy. What was largely dodged by all three parties is how fast this would happen, and what sacrifices would need to be made. The Conservatives pledged to reduce carbon emissions to net zero by 2050, Labour and the Scottish Nationalists by 2040, with the Scottish Nationalists adding an additional interim target of a 75% reduction by 2030. These targets are all comfortably far off in the future: even the closest one (2030) will be at least two more General Elections away, and by the furthest one (2050) most of the politicians elected this month will be retired or dead. If the targets aren’t met, there are lots of opportunities for deflecting the blame onto someone else. What was left unsaid by all three parties was how much they are going to reduce carbon emissions in the next 12 months, or by the end of the 5 year life of this parliament, because that would be too easily measurable and accountable. Taking the least ambitious target (net zero carbon emissions by 2050), a back-of-an-envelope calculation suggests that we would have to reduce them by an average of 3-4% per year, starting now. So can we expect to see a 3% reduction by the end of 2020, or a 16% reduction during the 5-year term of this parliament? Nobody wants to say.

Also, net zero carbon emissions would mean either zero air travel, or sequestering 100% of the carbon emitted by aeroplanes. At the moment we have neither electric aeroplanes nor the capability of sequestering that much carbon. A search for the phrases “air transport” and “air travel” reveal that neither of these phrases are mentioned in any of the manifestos.

So do I think these promises of “zero carbon” and “clean energy” will be met? In a word, no, although the Scottish Nationalists are walking the walk to some extent: Scotland already has hundreds of wind turbines and is continuing to build more.

Economy

Both politicians and voters seem to be functionally illiterate when it comes to the economy. The Conservative manifesto mentions the word “growth” 21 times, as in “we will deliver economic growth, not just through the 2020s, but for decades to come.” (page 7). The SNP manifesto makes frequent reference to “sustainable growth” and also promises to grow the Scottish population. However, the Labour manifesto is surprisingly muted, mentioning “growth” only twice. The voters fell for the “growth” narrative hook line and sinker, and punished Labour for not promising it.

Infinite growth on a finite planet is impossible, so the Conservative promise of perpetual economic growth cannot, and will not, be kept. Nor is “sustainable growth” possible; in fact it’s an oxymoron (two contradictory terms appearing together). Something which is growing is not sustainable, because eventually it will run out of resources and stop growing. The only kind of growth which is sustainable is cyclical or regenerative growth, like a forest, where as new trees grow, old trees are decaying and dying at the same rate and forming the raw material for new trees, so the whole system is in balance. However, that is absolutely not what politicians mean when they talk about “sustainable growth”.

What is actually going to happen to us, whether we like it or not, is de-growth or contraction. The planet can’t support any more growth in the traditional 19th and 20th century model, and can’t even support our present level of consumption. Nobody who wants to get elected is talking about that.

Environment

With growing public awareness of climate change, no political party can avoid talking about the environment; however, what they are actually going to do about it is another matter. The Conservatives express vague aspirations to “lead the world in tackling climate change”, which they plan to do mainly by achieving the target of zero carbon emissions by 2050, which as I have already said, is probably not going to be achieved, and by planting 75,000 acres of trees a year. Labour plans a “Green Industrial Revolution” and will instruct the Committee on Climate Change to recommend policies (hang on, I thought your manifesto was where you were supposed to recommend policies…?), and plant a total of 1 million trees. The SNP accepts that there is a “climate emergency”, makes frequent references to it throughout the manifesto, and promises to plant 60 million trees a year.

There’s nothing wrong with planting trees, and it’s nice to see all the parties trying to outdo each other with their tree planting promises, but it’s difficult to see on what land they would plant these trees, because Britain is a crowded island and nearly all land is already being used for something. If fossil fuels become scarcer and more expensive in the future, we will need to move to a less intensive and more localised farming system to produce our food, which will require more land, which will compete with the land needed for tree planting. Also, if we are planning to grow the economy and the population, we will need more land for roads, houses, shops, schools, factories, mines and so on.

In conclusion, I don’t think any of the parties are being honest with the public about where the future is taking us or what needs to be done. So for the next five years it’s likely to be business as usual as we speed ever closer to the cliff edge.

Good luck.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

References

Allotment

So here we are in autumn, the “Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness” according to the poet John Keats. I am going to write today about my first season of growing food on an allotment, but I want to start with a brief and serious warning: there are food shortages coming. The world’s population is currently 7.7 billion, increasing towards 8 billion and more. For the last 12,000 years since agriculture was invented and crops and animals domesticated, and up until about 100 years ago, food production was powered by human and animal muscles. Today most of our food supply is dependent on fossil fuels at every stage, including production of fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides, sowing, harvesting, processing and transporting to the end users. Those fossil fuels are depleting. Global reserves of phosphorus, an important component of fertiliser, are depleting. Topsoil is depleting. Fish stocks are depleting. Aquifers are depleting, such as the great Ogallala aquifer under the Great Plains of America. Mountain snow packs which feed into great rivers such as the Indus are depleting. There will be water shortages making irrigation of crops problematic. Climate change is causing weather instability and rising sea levels. Climate zones suitable for agriculture are slowly moving away from the equator and towards the poles, and arable land is slowly turning into desert, salt marsh or flood zone.

All of these threats suggest a global food shortage in the not too distant future. We probably won’t have enough food for 8 billion, or 10 billion, or however many people we have at the time it happens. Nobody will be spared, although some people will fare better than others, particularly if they are very rich, or live in a rich country. I can’t say when this will happen, maybe in the next 50 years, maybe in the next five, but it will happen, and people need to prepare for it as best they can. My way of preparing for it is by learning how to grow my own food.

I felt obliged to give you that warning, what you do with it is up to you, and now we shall speak of it no more and I will tell you about my allotment.

Most British people will understand what an allotment is, but for readers in foreign parts who may be less familiar with the term, I will explain. An allotment is a piece of land, typically about 30 x 100 feet, which is rented for the purpose of growing flowers, fruit and/or vegetables for the allotment holder and his family. Although some allotments have existed since the 1700s, they were particularly popular during the Victorian era and the First and Second World Wars as a means for poor people to grow food for themselves. In Britain, allotments are often on marginal land, for example at the edge of town or along railway tracks, which would not be suitable for other purposes.

In the picture above, please observe the carefully manicured grass, the weed-free pathways and the line of fruit trees standing to attention. This is my neighbour’s allotment. I wonder if he has issues with obsessiveness. Perhaps I should ask him, in a supportive and non-judgemental way, whether he would like to talk about this.

And this is my allotment. Above is a picture of my allotment when I first took it over in March this year: a weed-and slug-infested wilderness.

And here is a picture of my allotment at the end of my first season: a weed- and slug-infested wilderness which now has some polytunnels and a shed on it. In order to explain how I achieved this amazing transformation, I have distilled the lessons learned in my first season into Ten Commandments For Allotment Beginners.

First Commandment: Follow The Herd

Observe what everyone else is doing. If everyone else around you is growing onions, potatoes, rhubarb and raspberries, that is what you need to grow. If they cover their crops with bird netting, go get some bird netting. If they start digging up their potatoes, that is a sign for you to go and get a spade and do the same. Once you have more experience, by all means experiment with doing things differently, but for now there is safety in numbers.

Second Commandment: Plant Stuff In Straight Lines

I’m not talking about approximately straight lines – I’m talking about exactly straight lines to within a few millimetres. This is important because the weeds grow much faster than the crops, and weeding is a lot easier if you know where the stuff you planted is and where the weeds are. When they first start growing they all look the same. Leave yourself enough room to get a hoe down between the rows.

Third Commandment: Visit Your Vegetable Patch Every Day

It’s much easier to keep on top of the weeds with a bit of hoeing every day, than to let it go for a few weeks and find the weeds have smothered your crops. Also, if you spot problems when they first occur, you have a better chance of correcting them. For example, if your crops start to look a bit dehydrated, watering them early will fix the problem, but if you come back a week later and find a row of brown shrivelled sticks where there were once plants, it’s too late. However, this may be a counsel of perfection, because if you have a full time job like I do, you may not have time to inspect your vegetables every day. In which case…..

Fourth Commandment: Plant Your Patch According To Your Time Available

There are two ways of doing this. Some gardening books recommend starting by planting only a small part of your available plot, and gradually expanding it if time permits. I can see the wisdom in that, but I would favour a slightly different approach, which is to use the whole of your available plot but plant it with things which don’t need much looking after. I have a 30 x 100 foot plot, and for my first season I tried to plant the whole thing with vegetables. However, I have a full time job, and I could only visit the plot for half a day a week, if that. This didn’t work out at all well, because while I was planting one part of it, the weeds were growing thick and fast in the part I had previously planted, and I just couldn’t keep on top of it. So for next season I am planning a much less labour intensive plot, comprising: fruit trees on half of it, fruit bushes and strawberries on a quarter of it, and vegetables on the remaining quarter. The fruit trees, fruit bushes and strawberries are perennials, which means they only need planting once and then they come up every year, which is much less labour intensive than continually replanting vegetables.

Fifth Commandment: Take What You Read With A Pinch Of Salt

I have read lots of gardening books, some of which give conflicting advice. For example, permaculture manuals favour the “chop and drop” type of weeding and pruning, which means that when you cut or uproot something you don’t want, you just let it drop onto the soil and decompose where it lies to feed the next generation of plants. Sounds great. However, the more traditional gardening books tell you not to leave dead plant litter lying around because it acts as a shelter for pests: rake it up and put it in a compost heap to decompose. Having tried both, my research suggests that the traditional method is best: put it on the compost heap, otherwise you are just creating a sort of slug hotel. Sorry permaculturalists, but if you think I’m being unfair and not doing it right, please let me know.

Sixth Commandment: Use Lots Of Physical Barriers

I soon discovered that there are lots of critters and wee beasties who are happy to gorge on my stuff all day long, because they don’t have full time jobs like me and they have nothing better to do. I’m trying to avoid using chemicals to keep them off, but that means I need to use more physical barriers. These include bird netting, rabbit proof wire netting, polytunnels, slug repellent tape and so on. This can be a significant additional cost in the first season, but after that you can use the same physical barriers over and over again.

Seventh Commandment: Wildlife Is Great, But Not In The Vegetable Patch

I took one of my kids to see the allotment, he was thrilled to find some slug eggs and wanted to bring them home to see if they hatched into baby slugs. Er, right. I was hoping he would learn about growing things, but that wasn’t exactly what I had in mind. Of course I understand that slugs are fascinating, and as one of God’s creatures they have as much right to exist as I do, but not in my vegetable patch or home, thank you.

Eighth Commandment: Get Some Solar Powered Muscle

Hand weeding is very hard work, so to help out with this I have an electric strimmer (line trimmer / weed whacker) and electric lawnmower. The strimmer is designed to be plugged into a mains electricity supply, of which there isn’t one at the allotment, so I run it off a separate deep cycle battery and inverter. The lawnmower has a built in battery. Both of the batteries can be charged from a photovoltaic panel, which is an important consideration if you are thinking of using them in a “grid down” situation, but for now I find it easier to take them home and charge them there.

Ninth Commandment: Organise Your Compost

Composting is a very important part of gardening, because when you grow things, you are taking nutrients out of the soil, so you have to give some thought about how you are going to put them back in again. However, you need to have an organised system. Ideally you need at least four compost piles: a pile of “normal” garden waste, a pile for the nastier stuff like the roots of perennial weeds which need to be either burnt or composted for a long time to make sure they are dead, and two similar piles which you made last year and which should be about ready to be returned to the garden. If you eat some of the plants you grow, then unless you are planning to poop on your compost heap, this represents a gradual loss of nutrients out of your garden, so at some point you have to replace them, for example with fertiliser or farmyard manure. One of the problems with modern industrial farming is that there is a continuing massive loss of nutrients from the topsoil, because most human waste is not returned to the land, so this has to be made up with artificial fertilisers which will some day run out. On my allotment, the weeds grow so vigorously that I have ended up with several massive compost heaps. I just hope they turn into compost before my soil runs out of nutrients.

Tenth Commandment: Grow The Right Amount Of Stuff

This is a very tricky one to get right and it can only be done with experience. You don’t want to end up with so much of one type of food that you can’t eat it all. On the other hand, you don’t want to end up with so little food that it’s pointless: for example, if you have a family of five and your strawberry patch only produces four strawberries at a time, that’s not much good either. Some plants, for example lettuce, produce a lot of food from a small area. Other plants, for example peas, produce a small amount of food from a large area. So for every row of lettuce, you probably need to plant about four rows of peas. An excess of food can be preserved, but that is a lot of hard work and really it’s best to try to get the quantities right so you can eat it freshly picked.

Well, those are some (but not all) of the things I have learned this season. It’s been a steep learning curve, and I haven’t had nearly as much food out of the allotment as I’d hoped, but that’s the reason for practising these skills before you need them. If I had been relying solely on my allotment to feed myself, I’d be dead by now, even though it is probably capable of feeding me in theory. I’ll give you an update this time next year about how my second season goes.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

P.S. The following picture shows the “used tyre” method of gardening as practised by another allotment holder – see discussion in Replies.

Carbon Capture and Storage – A Fairytale for our Time

I was browsing the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) news website recently when the following item caught my eye:

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/cnrl-steve-laut-ghg-net-zero-1.5221740

It’s a good news story about how Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNRL), Canada’s largest oil and gas producer, is hoping to reduce CO2 emissions from its tar sands operations to zero by using new technologies such as Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) projects. The implication is that if we can deploy this technology on a large scale, business as usual can continue, because we can burn all the fossil fuels we want but leave the resulting CO2 in the ground. What’s not to like about that?

So what is CCS and how does it work? Here is a video by Shell explaining how it works:

https://www.shell.ca/en_ca/about-us/projects-and-sites/quest-carbon-capture-and-storage-project.html

In brief, CO2 is captured from the processing plant, pressurized to turn it into a liquid and transported by pipeline 65 kilometers to a number of well sites. The still-liquid CO2 is then injected more than two kilometres underground into a layer of rock filled with interconnected pores. The CO2 becomes trapped within the pores, and the layers of watertight rock above it stop it from escaping. Constant monitoring both above and below ground makes sure the CO2 stays safely and permanently in place. Get that – permanently. Forever. Over one million tonnes of CO2 are being captured and stored in this way each year, and four million tonnes have so far been captured and stored during the course of the project.

That’s the industry side of the story. But is it true? I have several concerns about it, including that little word “permanently”. I don’t see how you can inject highly pressurised, liquefied gas underground at a rate of one million tonnes per year and expect it to stay there “permanently”. The laws of physics and common sense suggest that it is going to find its way to the surface.

They say that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. By the same token, an underground reservoir is only as gas tight as its leakiest part. And if you have a reservoir hundreds of kilometres wide, how many leaky parts are there going to be in that?

So I decided to investigate further. I contacted CNRL and asked for the pressure readings in the reservoir before, during and after the CO2 injection process. If the pressure in the reservoir failed to rise significantly while the gas was being injected, or rose during injection but then fell afterwards, either of those scenarios would suggest a leaky reservoir. It’s like pumping up a bicycle tyre: if you pump up the tyre but it rapidly goes flat again, you know there’s a hole in it.

The CCS facility appears to be a joint operation between Shell, CNRL and Chevron. I contacted Shell first. They suggested I contact CNRL. So I contacted CNRL. They suggested I contact Shell. This initial run-around did nothing to boost my confidence in the project. But eventually, after sending a third firmly-worded email, I got a response on behalf of Shell from Stephen Velthuizen, External Relations Manager for the Scotford Upgrader, of which the CCS project is a part. Essentially what he says in response to my questions about reservoir pressures is this:

- There is minimal pressure rise during the injection process, from a baseline pressure of 19.5 MPa (megapascals) to 20.5 MPa after injecting 4 million tonnes of CO2. These pressures are equivalent to 2,828 and 2,973 psi (pounds per square inch) respectively. For comparison, a bicycle tyre would typically be inflated to 50-130 psi.

- He wasn’t willing to give me any figures for how rapidly the pressure decays after the CO2 injection stops.

- In his own words: “But pressure alone – while an indicator – is not the only way to assess what is happening in a reservoir. One of the many technologies we use to monitor the CO2 is vertical seismic monitoring. By comparing a current vertical seismic profile (VSP) to our pre-injection VSP, we can detect the CO2 plume (through the variance). The VSP can also detect CO2 that has migrated out of the reservoir. The monitoring of many factors allows us to identify if a leak is occurring and take corrective action. We also have deep monitoring wells above the reservoir that provide valuable pressure information to indicate if a leak was present.”

I’d be very interested to hear from any readers who have expertise in geology or the operation of high pressure wells. I don’t – I’m just a simple family physician. But what Mr Velthuizen is saying sounds to me suspiciously like poppycock. I don’t believe a word of it. If you inject 4 million tonnes of gas into a reservoir, and there is hardly any rise in pressure, then surely common sense suggests that there is a leak: not just a small leak, but a massive leak, a leak so big that the gas is leaking out almost as fast as it can be pumped in? Like trying to pump up a flat bicycle tyre which obstinately remains flat? And all that talk about vertical seismic profiles and CO2 plumes sounds suspiciously like misdirection, which is what stage magicians do: they direct your attention to what they want you to see in order to direct your attention away from what they don’t want you to see.

Wishful thinking is a powerful emotion. That’s why the media and the public love a good news story like this and don’t ask too many questions. We really wish we had a magic wand to wave that pesky CO2 away so we can carry on flying our jets, driving our SUVs and eating food from the other side of the world with no consequences. We really wish that CCS would be that magic wand. The problem is that as far as I can tell, it probably doesn’t work.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

Reaching Out to the High Priests

Once every couple of years I contact a prominent opinion leader whose views are very different from my own, and attempt to engage them in dialogue with a view to either changing their opinion, or allowing them to change mine. I’m talking about government ministers, church leaders, university professors, those sorts of people: the modern day High Priests of our society, who set the standards for what people are supposed to think, and the boundaries of acceptable discourse. I have had a success rate of zero so far, because nobody’s opinion has ever moved an inch, but I do it out of a sense of moral obligation, probably for the same reason that people glue themselves to buildings in defence of the environment, or volunteer in soup kitchens, or help to clear landmines; it just seems like the right thing to do. You could call it “outreach” or maybe “missionary work”.

I’m not one of those cranks who constantly churns out letters, by the way: I find the process quite disheartening, so one letter every couple of years is enough for me. However, I think it’s good for me, because in order to find out what these people’s views are, I have to read their material which I don’t necessarily agree with. I also think it’s good for them, because I suspect that most of the time they live in an echo chamber in which the only opinions they hear are their own and those of people who agree with them, and it’s good for them to know that there are alternative points of view.

The first time I can remember doing this was when I was about seventeen and I wrote to our local Catholic bishop suggesting that the Catholic church should encourage contraception, because the human population can’t continue expanding forever, and we therefore need some humane way of keeping our numbers in check other than the traditional methods of war, disease and famine. His reply was along the lines of “God said ‘Be fruitful and multiply’, we don’t know how many people the Earth can hold, therefore we should keep increasing our numbers until we hit that limit”.

40 years later, there are so many red warning lights blinking on the dashboard that I think the bishop’s limit has been reached: look at, for example, loss of habitat, loss of biodiversity, species extinction, resource depletion, air and water pollution and climate change. If God could speak to us today, He would probably say something like “Guys, I know I said ‘Be fruitful and multiply’, but I didn’t mean for you to take it literally and wallpaper the planet with people; you can stop now.” Unfortunately, we will never know what the good bishop thinks about it now or whether he has changed his mind, because he has long since met his God and hopefully had that conversation directly with Him.

I have written to a British Roads Minister asking whether he accepts the (widely accepted) view that building more roads will never solve traffic congestion because it just encourages more people to drive more cars more often – a phenomenon known as Jevons’ Paradox. (Result: three evasive replies without actually answering the question).

I have written to the Bank of Canada suggesting that their forecasts of a perpetually growing economy can’t possibly be correct, because over time the economy would grow so large that it would need to consume infinite resources. (Result: three evasive answers culminating in a statement that their economic forecasts only look two years ahead, so what happens after two years is unknowable and/or irrelevant).

I have written to the Professor of Inclusion and Diversity at a prominent North American university, informing him that I had done a Google search for “insane university political correctness”, congratulating him on the fact that his name and department had come top of the search list, and asking him to clarify some of the more, let’s say, unusual news reports in which he and his department had recently featured. (Result: no reply).

My latest attempt in this vein was a letter to Philip Aldrick, the Economics Editor of the London Times, asking for clarification of an opinion piece he wrote recently. Mr Aldrick is a prominent financial journalist who has won many awards including Business and Finance Journalist of the Year, and who is in demand as an after dinner speaker for corporate events. You can read part of Mr Aldrick’s article here (the rest is behind a paywall):

and here is the text of my letter to him:

“Dear Mr Aldrick

I was interested to read your recent Times article “IMF cuts global growth forecast to joint lowest since crisis” (10 April). There is just one thing puzzling me though. The original forecast (before downgrading) was for 3.5% global growth. If this was continued over an average human lifetime (80 years), the global economy would have to grow by a factor of 15, and if it was continued over two lifetimes (160 years) it would have to grow by a factor of 245. I can’t imagine the world producing and consuming 245 times, or even 15 times, the energy and materials it currently consumes, so surely this 3.5% forecast was destined to stop at some point anyway?

This is a very simple calculation – just a compound interest calculation really – and yet whenever economists talk about growth, this logical long term implication is never mentioned. Can you tell me why this is?”

Result: no reply. Mr Aldrick is probably a busy man with his after dinner speeches and opinion pieces and the like, and probably doesn’t have time to engage in correspondence. It would be like expecting a reply from the Pope, or the Buddha, or the Inca Sun God. So, continuing in the religious vein in which I started, I’d like to round off this blog post with a parable, defined in the dictionary as “a simple story used to illustrate a moral or spiritual lesson”. All persons in this parable are fictitious, with any resemblance to any real persons, living, dead or not quite dead, being purely coincidental.

This is the story of Mr Right-Thinker and Miss Wrong-Thinker. They both graduated in the same year with a first class degree in Media Studies from a prestigious university. Both were keen to pursue a career in financial journalism and went to work for the same national newspaper. There was, however, one important difference between them. Mr Right-Thinker believed that business people and economists should always aim for economic growth, and that this growth could continue forever because market forces and business entrepreneurship would always overcome resource scarcity. Miss Wrong-Thinker, on the other hand, believed that infinite economic growth on a finite planet was impossible, and that business people and economists should aim for a steady state economy which neither grew nor contracted, and make products which lasted a long time so people didn’t have to keep buying new ones.

The editor of the newspaper was always pleased with Mr Right-Thinker’s work, because the two men always seemed to think along the same lines. Miss Wrong-Thinker’s work, however, was frequently returned to her for multiple corrections, or not published at all.

Slowly but surely, their careers diverged. Mr Right-Thinker was sent to cover important international conferences on the economy. Miss Wrong-Thinker could not be trusted with such important assignments, so she was sent to cover local council finance committee meetings.

On the international conference circuit, Mr Right-Thinker met many important people such as wealthy investors and businesspeople, top rank politicians, celebrities and newspaper proprietors, who were impressed by this rising young journalist’s financial astuteness. He had a knack of telling them exactly what they wanted to hear. They started to invite him to their private dinner parties, where he met even more important people.

Miss Wrong-Thinker sometimes went for lunch at local restaurants with the local councillors.

One of Mr Right-Thinker’s new contacts put his name forward to be a guest speaker at an international financial conference. His speech was a great success, following which he found himself in demand as a public speaker. Politically astute, he was careful always to please his audience by telling them that they were doing exactly the right thing, and consequently he was always invited back to give more speeches.

Miss Wrong-Thinker was invited to give a speech to the school leavers from her former high school about “How To Become A Journalist”.

Mr Right-Thinker’s career continued to progress by leaps and bounds. His ambition is to become editor of his newspaper when the current editor retires. He continues to earn £5,000 for each speech he gives.

Miss Wrong-Thinker gave up full time journalism, telling herself that she was never much good at it anyway. However, she keeps her hand in by writing a weekly “Wildlife Watch” column for the local paper, for which she gets paid £50 each time. She got married and had two children, and her ambition (rarely achieved) is to get all the laundry and housework done by the time the children come home from school.

You may think that Mr Right-Thinker’s career has been much more successful than Miss Wrong-Thinker’s, and you may be right. However, there is one small dark cloud on the horizon of Mr Right-Thinker’s shining ocean of success. He can never, ever, change his mind. If he admitted publicly to any doubts about the wisdom or practicality of perpetual economic growth, his friends, contacts, dinner party and conference invitations, reputation and income would melt away like snow in the spring, and he would be replaced by someone more “on message”.

Here ends today’s parable. May your God go with you.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin